Dr. Nanette Wenger, the queen of hearts

By Laura Williamson, American Heart Association News

Open Dr. Nanette Wenger's refrigerator, and the first thing you'll see is a bowl of ice chips filled with crudités – carrot and celery sticks, perhaps some broccoli florets.

"I love them," said Wenger, the world-renowned cardiologist who turns 94 this year. "I've always eaten healthy."

Wenger says she still weighs the same as the day she was married more than 60 years ago, and she isn't afraid to give you that number: 110 pounds. She never smoked. She's a light drinker. Her blood pressure, cholesterol and blood glucose levels remain in the healthy range. She stays physically active, but as a physician, she never had to look for ways to fit exercise into her day.

"When you do clinical medicine, getting 10,000 steps a day was just part of your routine," Wenger said. "There were days when I didn't sit down for three or four hours. I think I was part of the heart-healthy regimen before it was named that."

Being a pioneer comes naturally to the woman known for so many firsts.

Wenger was one of the first women to attend Harvard Medical School. The first woman fellow and chief resident at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City. One of the first to understand the best way to recover from a heart attack was to get out of bed, not stay in it. And the first and most forceful voice to call for greater inclusion of women in medical research to understand the unique way cardiovascular disease affects women.

After seven decades as a clinician and researcher, Wenger isn't just still healthy, she's still working.

"What else would I do?" she asks when people wonder why she hasn't retired. Wenger remains a professor of medicine in the division of cardiology at Emory University School of Medicine, a consultant to the Emory Heart and Vascular Center and founding consultant to Emory Women's Heart Center in Atlanta. She began working at Atlanta's Grady Memorial Hospital in 1958, where she became director of cardiac clinics and never left.

Being a doctor is what she has wanted to do for as long as she can remember. She is cardiovascular royalty. The queen of hearts, if you will.

Wenger is literally why women's heart health is a thing.

It never occurred to Wenger that she couldn't – or wouldn't – be a doctor. Born in 1930 to Russian immigrant parents who settled in New York, she grew up with the message that she could be anything she chose to be. Since she loved her high school science classes and she loved people, it made perfect sense to her to combine her passions into a career in medicine.

"I had a number of cousins much older than I was who were doctors, all men," she said. "They seemed to so thoroughly enjoy what they were doing. My father had a sister in Russia who was a surgeon. He always talked about her with great admiration. He had another sister who was a pharmacist. In our family, this was not regarded as unusual." (It's a tradition she passed on. Two of her three daughters are doctors, and the third is a dean at the University of Pennsylvania.)

Wenger entered Hunter College in New York City as a pre-med student, convincing her parents to let her take the Long Island Railroad into the city by herself each day, an almost unheard-of activity for a young woman in the late 1940s. "I persuaded my parents that it was perfectly appropriate," she said.

Wenger would spend much of her life convincing her elders and authority figures to listen to, and accept, her bold ideas.

After graduating summa cum laude from Hunter in 1951, she was accepted to Harvard Medical School, where a small number of women were being admitted under a 10-year probationary period that would end when her class graduated in 1954.

"Because we were probationary, we could not get university housing," she said. "So, we lived in apartments in town, which was wonderful."

Wenger never felt discriminated against as a woman at Harvard, even though "the faculty really did not know how to handle us," she said. "The men were very, very supportive. I had a wonderful time in medical school. We all worked hard. It was a very exciting time, particularly for cardiology."

Working on the frontier

Wenger was becoming a cardiologist at a time when great strides were being made in cardiovascular research, a field then in its infancy. "This was just the beginning of cardiac pharmacology and surgery," she said. "We began to feel as if we were on the frontier, and that was exciting."

Two of the biggest influences on her medical training were world-renowned cardiologists Dr. Louis Wolff, with whom Wenger interned for three months at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston, and Dr. Charles Friedberg, chief of cardiology at Mount Sinai.

"I made rounds with him every day for a year," she said of Friedberg. "He was a superb clinician."

Initially, some of Friedberg's patients were hesitant to be treated by a woman, Wenger said. "When they would back off at being seen by me, he would smile and say, 'This is the physician who is going to guide the medical care for your children and grandchildren.' That had an amazing effect on these patients, and suddenly I became acceptable."

Challenging the status quo came naturally to Wenger, who never hesitated to make changes when she thought they were warranted, no matter how controversial.

She reportedly began making waves as soon as she arrived at Grady Memorial, where she went to work alongside her husband, gastroenterologist Dr. Julius Wenger, in 1958. At the time, the hospital was segregated. White patients were addressed as "Mr." and "Mrs.," while Black patients were addressed by their first names. Black nurses were simply called "nurse," given no name at all.

Wenger refused to follow that rule, addressing everyone with the same respect, even though she was called into the hospital director's office for doing so. She explained why she did it in a 2017 interview with Forward, a Jewish newsletter. "It was a tiny step, but it salvaged my sense of what was right and what was wrong," she said. "I just could not abide by people not being treated as equals. Everyone has core values, and those were mine."

'Where are the women?'

It was in Atlanta that Wenger made what was to be her biggest contribution to cardiovascular medicine and created what would be her legacy – the recognition that heart disease behaves differently in women than in men and should be studied accordingly.

At the time, heart disease was considered a man's disease. But Wenger was seeing female patients at Grady who complained of chest pain and were having heart attacks. She looked for more information on how to treat them.

"When I went to the literature, all I learned about was men," she said. "There was absolutely nothing to guide me for treating women. The model for all the interventions was a middle-aged man. It was thought to be translatable to everyone else, but I wasn't sure that was the case."

She took her curiosity to Framingham, Massachusetts, where the first long-term study of cardiovascular disease risk was taking place.

In Framingham, researchers concluded that for women with angina – or chest pain – this was not considered as serious as having a heart attack and was believed to be benign in women. "I realized that no one had ever bothered to study these women with angina," she said.

"So I went to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and I was asking questions and really no one was particularly interested. I was part of a research project that looked at cardiovascular risk, but it involved only men. I said, 'Where are the women?' And I was told, 'The women are just too complicated for this. They have hormonal issues.'"

Frustrated, Wenger coined the term "bikini medicine," referring to the medical field's myopic focus on the parts of a woman's body found under her bikini. "The research on women's health was focused on their breasts and reproductive medicine. I said it in jest, but other people picked it up."

And then she set out to change it.

Wenger convinced NHLBI officials to explore the issue at a 1986 workshop on coronary heart disease that she co-chaired. It took her six more years to convince them a full conference was needed, dedicated exclusively to cardiovascular disease in women, which she co-chaired in 1992. That led to a special article the following year in the New England Journal of Medicine summarizing recommendations from the conference, including the need to recognize angina in women as a flag requiring further evaluation for coronary heart disease, dispelling the myth that it was harmless.

"We outlined all of the knowledge gaps and that sparked interest in many, many people," she said.

Wenger did more than introduce the idea that heart disease in women required a deeper look. She pushed for women to be included in all cardiovascular research and for findings to be analyzed by gender. Guidelines encouraging the inclusion of women in clinical research were established in 1986 but did not become federal law until 1993.

She also pushed for studies that looked solely at women's cardiovascular health, building a career around finding answers to questions about how it differed from men's and generating new questions to explore. "She continued to look at that question in multiple different ways," said Dr. Mary Norine Walsh, medical director of heart failure and cardiovascular research at Ascension St. Vincent Heart Center in Indianapolis. "She was looking at different disease states and risk factors like hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Her early work, her seminal papers were all on that."

Wenger's ideas about women's cardiovascular health differing from men's "were not well received," said Walsh, a past president of the American College of Cardiology. "She was really shouting into the stratosphere, and people were like, 'What are you talking about?' Now everyone knows this, but then no one knew it."

Wenger remembers how her mentor at Emory, Dr. J. Willis Hurst, reacted when she wouldn't back down from her push to learn more about how heart disease affected women.

She recalled him saying, "'You have such a good reputation. Don't go off on this tangent.'" But she told him it was important to her. "He said, 'I'll support you in doing this, but you're making a mistake.' A decade later, he came to me and said, 'I am so glad you didn't listen to me,' which was really the nicest thing any mentor can say."

Wenger said she never backed down because "I really thought it was important. And I persisted, and that persistence paid off. This is why when I advise junior faculty, I encourage them to go beyond their area of comfort, to think outside the box. If they think there's something important, to really explore it."

She was equally persistent about exploring how people should be treated following a heart attack. When she first entered cardiology, the standard treatment for someone who survived a heart attack was to keep them on bed rest. But at Harvard, one of Wenger's medical school mentors, Dr. Sam Levine, had started putting heart attack survivors in reclining chairs. She noticed that patients who got up and moved around sooner had faster and better recoveries than those who stayed in bed.

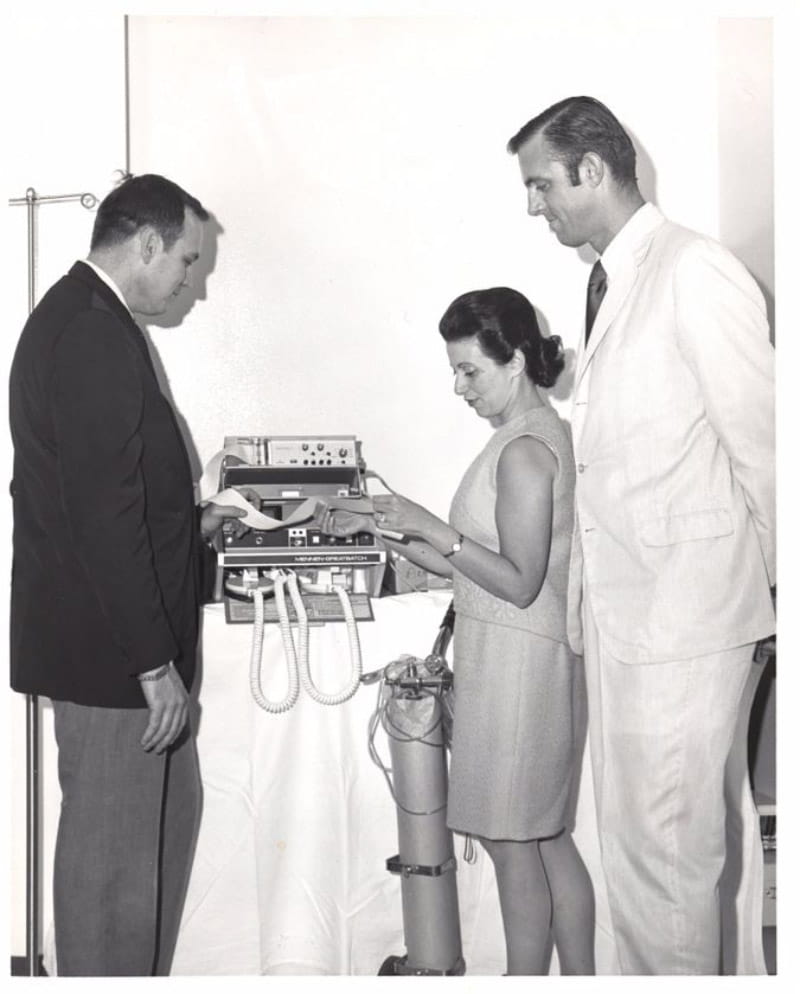

At Grady, she had patients sit up in bed and dangle their legs, attaching them to electrocardiogram monitors to make sure they weren't experiencing any dangerous heart rhythms. Getting them moving sooner allowed her to send them home from the hospital faster. This pioneering work contributed to the development of cardiac rehabilitation programs that today include regular physical activity to strengthen the heart and body and have been shown to lower the risk of dying in the years that follow.

Over the course of her career, Wenger has authored or co-authored more than 1,700 scientific papers, review articles and book chapters, chaired national and international task forces, conferences and committees, played leading roles in the American Heart Association, ACC and Society of Geriatric Cardiology, and received multiple awards for science, leadership and mentorship. She was one of Time magazine's "Women of the Year" in 1976. Emory University School of Medicine recently created a distinguished professorship in her honor.

Walsh remembers how surprised she was by Wenger's humility when she met her.

"Here she'd done so much and held so many titles and she came to me one day and told me she was going to apply for membership on an ACC committee on cardiovascular disease in women," she said. "It was our inaugural committee on this, and I was co-chair. And she said, 'I don't want to lead it, I just want to be a worker bee.' And that's Dr. Wenger to a T. She is not one for self-aggrandizement. You don't hear that too often from senior leaders when they're approaching a project."

Not only is Wenger a "collaborator extraordinaire," she actively encourages and supports younger researchers in pursuing new topics related to women and cardiovascular disease, Walsh said. "She has pulled forward more people to work in her field than most others have. The scientific world that we have now, with many focusing on sex-specific differences in cardiovascular disease, many of these people first started with her."

Her enthusiasm for what others are doing is genuine, Walsh said.

"She's gracious to everyone and interested in the next new idea," she said. "She's not a person who sits and tells you what her last project was. She's interested in your project."

And Wenger doesn't hesitate to recognize good work.

"You never do anything 'well' in the presence of Dr. Wenger," Walsh said. "She approaches you afterwards and says, 'That was spectacular.' She makes sure that she gives feedback to people who are junior to her, and that is everyone now."

Wenger said she is delighted to see younger generations continue the momentum for work she started so many decades ago. "Everyone has a leadership style. My leadership style is bottom up, not top down. I try to enroll people in my vision, which was women and heart disease. Then I let them explore what interests them. This is why I'm so excited to see this explosion of interest."

She pointed with pride to AHA's Research Goes Red Best Scientific Article award, which last year fielded 134 submissions published in AHA journals from research done in 20 countries, all focused on heart disease and stroke in women. "We're just seeing an explosion of interest from many researchers and scientists and clinicians," Wenger said.

In her most recent paper, published in Circulation in February, she notes that gender-specific research will be instrumental in addressing health care disparities but that much work remains to be done, especially in addressing disparities among racial and ethnic groups who are currently least able to identify the signs and symptoms of a heart attack.

She's disheartened that the hard-earned gains in awareness that cardiovascular disease is a major health issue for women have largely been lost, with awareness especially low among the groups most severely affected.

Her paper concludes with a challenge Wenger would like to issue to the next generation of researchers in women's cardiovascular health: "Investigate, educate, advocate, and legislate: investigate to establish a gender-specific cardiovascular data base; educate patients, communities, health care professionals, and other stakeholders; advocate to optimize appropriateness of public policy; and legislate to ensure health equity."

She'll be right there leading the way.